I failed to get something important done this week.

I really should have created a short survey (3, maybe 5 questions) for two different projects to share with you.

And yet I resisted doing it until the very last moment.

Now I need to postpone it for a week.

This is hardly tragic but as Rumi tells us:

The breeze at dawn has secrets to tell you.

Don’t go back to sleep.

You must ask for what you really want.

Don’t go back to sleep

Think of this newsletter then as a prelude to a coming ask––along with some thoughts on why reaching out for the opinions of others can be dangerous, irrelevant, and invaluable.

It’s been a while since I’ve seen it, yet I vividly remember the mysterious cosmic advice that drives the entire plot of Field of Dreams:

“If you build it, he will come.”

It’s easy to satirize the quote (like in Wayne’s World 2 when ghostly Jim Morrison appears to Mike Myers to announce “If you book them, they will come.”).

Yet nonetheless this thought embodies so much of how one is trained as a creative.

You tap into and hone your inner vision.

You express it, bringing it forth into the universe.

And you’re pretty much promised that if you do, the world must embrace your offering.

Unfortunately, perhaps more often than not, it just doesn’t work that way.

Even if you write it, no one might show up for your one-man show.

Or they may show up and have a lot of comments, many of them dazzlingly unhelpful.

Part of the resistance to asking people’s opinions too early in the game is because as a creative your role is to offer them something new.

Indeed, as the great Diana Vreeland, the legendary editor of Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue, said:

“You’re not supposed to give people what they want.

You’re supposed to give them what they don’t know

that they want yet.”

And there’s also the quote attributed to Henry Ford, the inspiring automotive pioneer:

“If I had asked people what they wanted,

they would have said faster horses.”

Stick to your groundbreaking vision, in other words, and ignore the focus group.

Speaking of which…

I remember many years ago when I was struggling financially.

A scrappy actor friend with some kind of marketing connectionsigned us for as many focus groups as possible.

They took only an hour or so and paid in cash, sometimes rather well.

Participation in any group was mostly determined by fixed criteria––age and gender––but there were certain areas you might be able tobluff your way around.

Somehow he got me selected for one that was tech-related but way, way beyond any knowledge I had.

I knew it was a mistake the moment they went around the room asking for opinions about various coding programs, none of which I knew.

I debated just quietly excusing myself but when the leader turned to me, in a stroke of desperate bluffing genius, I simply replied“Well, I’m an IBM guy.”

She filled in the blanks for me.

“OK. So you’re using _____ and ______, then?”

I simply nodded.

And it worked every time I was asked a question.

My unilateral (and imaginary) position even sparked an extended, spirited tech discussion, all of which was completely over my head.

I don’t think my charade caused any debilitating or disruptive ripples in the tech world and yet…

Embarrassed by my lack of integrity––yet very grateful for the necessary $300 it paid––that was my last foray into the focus group universe.

Actually, that’s not quite true.

Years later, I conducted a focus group for my own work.

My literary agent had been circulating an early draft of my novel.

We were getting very positive responses to the writing but rejections based on a few aspects of the main character’s vivid personality.

My agent and I thought the problem could be fixed by setting up a few story elements differently in the first 30 pages.

All of this feedback from publishers was happening when I was on a ten-day Caribbean Cruise with some core friends and some exciting new people I’d just met.

Everyone was on vacation and so it was an easy ask to rustle up a dozen target demographic readers.

All they had to do was read 30 pages on the beach and chat about it in my cabin later, bolstered with tropical cocktails.

A dear friend agreed to moderate the group so that people could speak freely without being inhibited by the author’s presence.

Afterward, my moderator friend related that one of my new cruise acquaintances—a smart and lovely young woman, reinventing her current life as an emergency room doctor and transitioning to becoming a full actress––was my harshest critic.

Absolutely nothing in the book worked for her.

She disliked the characters.

She hated the plot.

She found no charm or humor in the writing whatsoever.

Finally, my moderator friend thought to ask her, “What kind of novels do you like then?”

The strongly opinionated doctor/actress replied,

“None, actually. I never read fiction.”

Unless I was miraculously able to transform her feelings for the entire universe of narrative itself, gaining her approval was a battle I could never win.

As delightful as she was a dinner companion, listening to her opinion as a reader would have led me very, very far astray.

Sometimes the best response to intelligent feedback is simply to ignore it entirely.

At the same time, I’ve also experienced moments where just a touch of feedback changes everything.

Once a novice producer met with me to discuss a script I’d written.

He’d crossed out with big red X’s each of three scenes involving the main character’s brother.

I know it’s not quite the same thing as murdering a flesh and blood human, but it felt rather harsh and cold-blooded to have the brother eliminated from the script that ruthlessly.

Interestingly, the producer was right about the problem…but he had the wrong solution.

Rather than cutting the brother’s three scenes, the answer was that the brother actually needed more screentime.

All it took for him to take his rightful and important place in the story was two more brief moments on the page.

I learned an invaluable lesson about feedback:

Listen carefully when someone identifies a problem…

but it’s up to you to find the best solution.

Years ago, right after college, I attended a creative arts workshop weekend.

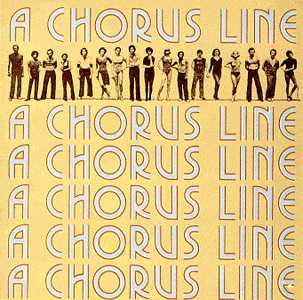

One of the participants was an extremely sexy older woman who shared that she was part of the original group of dancers around whose stories Michael Bennett created A Chorus Line.

When asked which character in the legendary show was based on her, she simply winked and said, “Dance Ten…Looks Three.”

And here’s the thing about that song (if you don’t know it, it’s HERE––you can thank me later.)

The song consistently flopped in previews until they changed its title.

I’m not going to tell you the original title but it’s the risqué part of the chorus, the saucy zinger that’s mildly shocking the first time you hear it.

They gave away the joke in the program, rather than onstage.

Now it’s part of showbiz history.

Nine Tony awards and a Pulitzer Prize later, sometimes the only feedback you need is to change three words in your song title.

It’s unclear whether Henry Ford ever said that quote about faster horses.

He did, however definitely say this:

“If there is any one secret of success, it lies in the ability to get the other person’s point of view and see things from that person’s angleas well as from your own.”

It’s approaching the situation from both perspectives––your vision and your audience’s reception––that creates real value.

Yes, there may be a non-fiction-only reader in the focus group for your novel (or even a tech guy imposter like yours truly).

And people don’t always know how to give feedback in sensitive ways.

(Remember it’s their job to identify the problems.

It’s your job to find the solution.)

And so…if I can overcome my resistance, next week maybe you’ll consider taking a brief survey.

I’d really appreciate it.

I’ll do my best to keep my perspective and also honor and learn from yours.

No pressure…but please remember, ultimately Vlad’s college fund is a stake.

Namaste for Now,