October Meditation is HERE.

I succeeded this week because, as the endlessly repeated pop culture meme posits, for once I actually understood the assignment.

More specifically, I got a perfect score on my final Executive MBA requirement, the Corporate Finance Case Study.

I correctly used Excel formulas to calculate Net Present Value (NPV) for three different scenarios.

The backstory of this exercise: to determine in which state––North Carolina, Pennsylvania, or Texas––I should locate my next cell phone factory.

(Note: This is entirely an academic exercise; I currently do not own any cell phone factories, nor can I help you with your current calling plan).

Here’s what you have to do to ace the case study.

You simply go with whichever state’s Net Present Value proves highest.

You calculate and examine but ultimately chose to ignore the IRR (Internal Rate of Return).

There are no other factors in your decision making process.

Even though the difference between the top two states was only 0.11%, that’s how I justified my decision of where to locate my next (again, utterly imaginary) cell phone factory.

I couldn’t help but marvel at how absurdly simplistic that decision making process was.

There are so many of other factors about whether I would want to locate my cell phone operations (or myself) in NC, PA, or TX.

And, more importantly, as I pondered further, I was reminded of how and why so many of my own personal decisions processes are inherently deeply flawed.

I’m also thrilled to announce that Vlad and I are back on the baseball field.

Well, almost.

Allow me to explain.

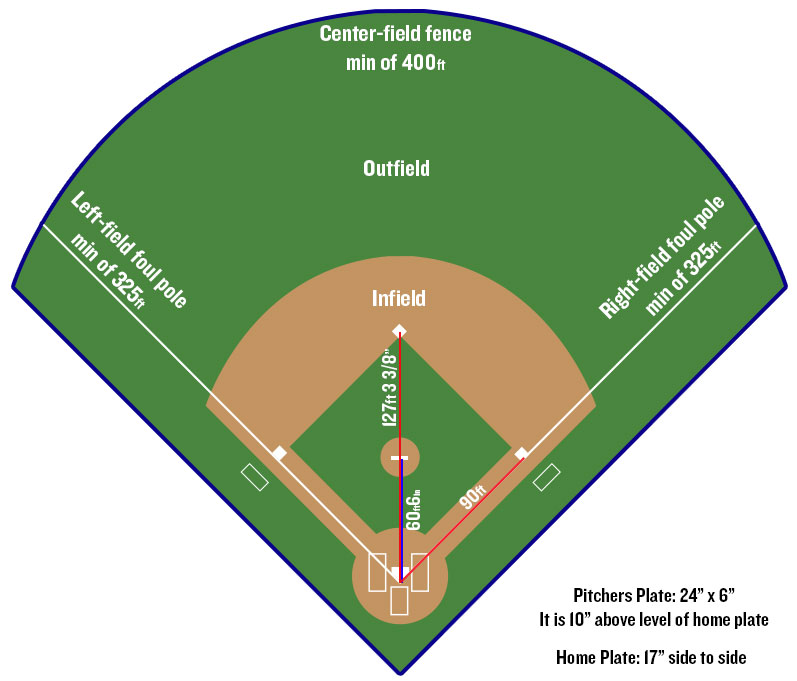

First, I’ve just learned from the MLB website that oddly (just like snowflakes) “No Major League ballparks are exactly alike.”

Even so “certain aspects of the field of play must be uniform across baseball.”

Thus, I inserted the graphic above to give you a little sense of perspective for my narrative recap.

You may recall that in July I shared that, near home base, Vlad saw an unleashed dog he suddenly wanted to play with just outside the park, walking parallel to the right field dugout.

Intoxicated, Vlad ran alongside the entire length of right field fence, then exited the park through the centerfield back entrance.

Returning moments later with a dopey grin, he has however, since that faux-jailbreak moment, obviously lost all his outdoor off-leash privileges.

Indeed, we spent most of the summer seeking other exercise outlets.

Yet something near-miraculous occurred last week.

I hesitate to say Vlad “manifested” this but the very same baseball field has undergone a major transformation.

The geography has changed and––at least from my perspective––only for the better.

More on that in a moment…

To correctly calculate Net Present Value, you’re instructed to always ignore Sunk Costs.

Sunk Costs are any money that’s already been paid and that cannot be recovered.

From the spreadsheet’s perspective, this makes complete sense.

Yet in real life, The Sunk Cost Fallacy (yes, the phenomenon has been thoroughly studied and even has a name) affects so many of our decisions.

Unfortunately, it almost always directs us in ways that are NOT in our best interest.

As a business example, if you spent $1 million on equipment to produce a gizmo that’s no longer marketable or becomes technologically obsolete, you repurpose or salvage what you can of the equipment.

You don’t keep producing the utterly useless item simply because you’ve already spent $1 million.

It goes against basic common sense.

Yet in our practical lives, almost everyone slips into the Sunk Cost Fallacy.

It’s the reason, even though 15 minutes in, you know it’s going to be boring and pointless––since you paid the full ticket price––you sit through the entire movie instead.

(It’s also the faulty reasoning behind why many people overeat at buffets or complete graduate programs in subjects they realize midway through that they hate.)

Once we’ve invested money, effort, or time in something, cutting our losses and moving forward feels counterintuitive, and more importantly, incredibly painful.

That’s why I believe Sunken Costs are most compelling and most damaging when it comes to our relationships.

Humans behave this way for many reasons, chief among that we havea commitment bias (we’re trained and rewarded to “stick it out”) and also a parallel aversion to loss.

Simply put, we’re hardwired to be more afraid of losing what we have than motivated by equal or greater gains.

Economists (and marketers) are very aware that Loss Aversion drives many of our business––and emotional–-decisions.

It’s not rational and certainly not strategic but it is nonetheless part of our nature.

In some ways, I’m reminded of what the great James Baldwin wrote about another kind of reluctance to let go:

“I imagine one of the reasons people

cling to their hates so stubbornly

is because they sense,

once hate is gone,

they will be forced to deal with pain.”

Holding on isn’t in our best interest, yet letting go somehow seems more frightening.

And that’s what keeps us trapped at a boring movie––or worse––ina painful personal narrative.

Speaking of bad trades…

I confess to having grown obsessed with Billions on Showtime, particularly with Bobby Axelrod, the ultimate ruthless trader.

One moment sticks out for me now.

In Season 4, Bobby flies his childhood friends via his private jet to see Metallica perform in Quebec.

One of his old crew from back in the day overhears a stock tip.

Hoping to capitalize on the moment, Bobby’s friend foolishly dives in without knowing the full, ever-changing situation.

Suddenly desperate for a bailout, the old friend appeals to Bobby for a $210,000 loan to save his skin.

With a phone call, Bobby rescues his friend from his bad trade.

The next morning, however, it’s revealed that Bobby and the others return via the private jet, having left the eavesdropping (and oversleeping) friend behind in the hotel room.

I find Bobby’s behavior fascinating.

He simultaneously saves his friend from ruin but also abandons him immediately thereafter.

He has a moment of nostalgia-inspired generosity, then he coldly calculates, cuts his losses, and swiftly moves on.

It’s both inspiring and terrifying.

Unlike Bobby Axelrod, this kind of ruthless subtraction when people and situations disappoint is not something I’m good at.

In fact, lately I’ve been spending a little too much time ruminating around personal Sunk Costs, particularly around troubling interactions.

And that’s why the theme of October’s new meditation is Letting Go of Loss.

You can find it HERE.

And now…back to Vlad and the baseball field.

Midsummer, six weeks after Vlad’s escapade, the entire morning dog community was shocked to find all the entrances to the baseball field were padlocked.

Except for official sporting event participants, no one could get on the field anymore.

The main entrance however––a parklet where one walks past a few benches and trees and a water fountain and (in the old days) on to left field––remains open.

There’s a newly erected fence that prevents you from getting on the field.

For me, it’s a godsend.

There’s only one way in and one way out of the pre-ballfield park and it’s solidly gated.

Knowing that he’d be safe, I brought Vlad back to his old stomping ground.

And I captured the moment below when Vlad stopped dead in his tracks as he first saw the newly erected fence.

That morning, dog after dog ran down those same steps only to have a total “WTF? Moment.”

Vlad looked to me for guidance.

Alas, I had no wisdom for him.

And I certainly couldn’t explain how happy I was by this new boundary.

Fortunately, it took just a moment, then Vlad more or less shrugged, picked up his ball, and got on with his life.

Vlad’s reasoning is quite sound.

So what if his square footage was reduced by 80 percent?

There was still plenty of room to run after the ball, chase Janey, and wrestle with Malibu.

Truly, none of the dogs seem obsessed with the loss of space.

Unlike us humans, they know instinctively not to incorporate regrets and losses into their emotional calculations.

Regarding this, it’s odd but when it comes to Sunk Costs, they behave much more rationally than we do.

Far beyond using the power of Excel on a spreadsheet––and more routed in realty than the dilemma of where to place my imaginary cell phone factory––they understand the assignment.

In each and every moment, they truly know how to calculate Net Present Value.

I hope the new meditation HERE helps us do the same.

Namaste for Now,