One part of what makes Awkward Beginnings — this month’s theme, meditation HERE — so challenging is that they often involve some variation of the burden of proof.

As every courtroom TV fan knows, legally this means convincing a judge or a jury, through a preponderance of evidence, that beyond a reasonable doubt some claim is true.

I have, however, recently been pondering other aspects of the word “proof,” since it keeps showing up in my life in multiple — and often ironic — ways.

First, let’s talk about books.

Since the earliest days of printing — from Gutenberg onward — a “proof” was a test impression of a typeset page.

Yet what was being checked was not the author’s work but the work of the press itself.

For hundreds of years, page by page, printers would run off a single sheet to check for errors in alignment, spacing, broken letters, missing lines, even ink smudges.

All of this was to ensure the page was ready for mechanical mass reproduction.

By the nineteenth century, however, the term “proof” was co-opted by writers and editors to refer to a near-final text: the author’s last chance to catch spelling and grammatical errors.

Proofing is now about fixing mistakes in the text, not the machinery.

In a way, the word is frozen in time — like “dialing” a smartphone or “filming” with a digital camera — its meaning shifting away from mechanical production.

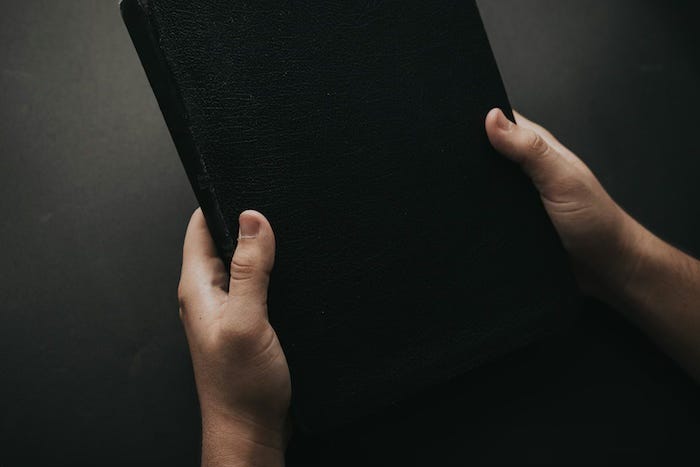

That same shift to the digital is what makes the experience of getting the first proofs — an actual physical copy of my new book — that much more thrilling.

Somehow, although you’ve been working on it for a year — and even though it weighs under a pound — once you’re holding it in your hands, it instantly becomes… real.

I’m also dealing with another kind of Awkward Beginning proof these days: Proof of Concept.

In a start-up context, a Proof of Concept (or PoC if you like business acronyms) is a small-scale test designed to demonstrate that your business assumption actually works.

An MBA way of saying that is that it’s “a limited validation of feasibility.”

On a more human level, a Proof of Concept is an experiment meant to answer one question: does this idea deliver what we hope it will?

It’s that painfully necessary bridge between theory and execution.

The Proof of Concept is not designed to prove that you can scale your idea or even make a huge profit — just that the core mechanism works, that your central premise holds up, that people want what you’re hoping to sell them.

That’s exactly what we’re gearing up to with the wellness app soon, a soft-launch to make sure our vision works in the real world.

Unlike proofs in publishing, however, this isn’t the dress rehearsal before a final reveal; it’s stepping out onstage to see if your dream has legs.

If you’re willing to stretch the premise, I suppose Proof of Concept could be extended to the art world as well.

For example, in 1962, Andy Warhol debuted his Campbell’s Soup Cans — a show of 32 nearly identical canvases — at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles.

They were priced at $100 each.

Even at that price, they didn’t sell, largely because most visitors thought the whole show was a joke.

It wasn’t until Irving Blum, the gallery director, realized that the whole collection made the most sense as a complete set.

He bought all 32 canvases for a total of $3,200 — paying $100 per month for 32 months (two and a half years).

Thirty-four years later, in 1996, Blum sold the entire set to the Museum of Modern Art for around $15 million.

Ten years later, another individual Campbell’s Soup painting sold for $11.8 million.

What are they worth now?

Over a decade ago, Vanity Fair estimated the 32 paintings were worth about $200 million; most experts now value them at over $320 million.

In a way, the Soup Cans were a brilliant proof-of-concept validation experiment — a test of whether an idea that blurred the line between high art and commerce had value.

The gallery exhibition = an unsuccessful prototype.

The public’s confusion = early-stage market resistance.

And the stunning proof of concept from that awkward beginning: those paintings are now valued at quite literally 10 million times their $100 initial price.

Here’s perhaps my favorite quirky variation in meaning around the word “proof.”

Nowadays, alcohol content in beverages is measured using precision instruments such as digital hydrometers, densitometers, or gas chromatographs.

In the 18th century, that wasn’t possible, so British excise officers created a simple field test to determine each spirit’s strength.

It was quite literally a test by fire.

The officers mixed a small sample of the liquor with gunpowder and tried to ignite it.

- If it failed to light, the spirit was too weak or watered down.

- Yet if it burned with a steady blue flame, that was “proof” that it was of serviceable strength — and deemed “100 proof.”

- Finally, if it exploded, that meant it was above proof — extra strong — and therefore taxed more.

Technically, 100 proof means that the alcohol volume is 57.15% — a clever merger of language, chemistry, and bureaucratic resourcefulness.

More importantly, as with all these uses of “proof,” the logic is consistent:

Test, Verify, Expand.

Perhaps the key takeaway for me this month is giving myself permission to have that awkward beginning.

How many of us are plagued with an Inner Critic that demands perfection right out of the gate?

Obviously, we know that’s impossible, and yet that voice can still hold us back.

As Voltaire wrote in 1772,

Le mieux est l’ennemi du bien.

“The best is the enemy of the good.”

It’s better to complete something and release it, flaws and all, rather than forever waiting in the wings.

Like Jennifer Beals in Flashdance, you may stumble at your big audition but still get the dance scholarship of your dreams.

What I love about all these quests for proof is that they encourage us to move beyond real or potential awkwardness in their beginnings.

Your gunpowder might fail to light — or it might explode.

Years ago, your book might have been a mess of overlapping letters and ink smudges; now it might be awash with embarrassing typos or a labyrinth of run-on sentences.

Those can all be fixed.

Or, believing that you’re not really serious about your art, perhaps no one will spend even $100 for one of your paintings; years later they’re worth $10M each.

(Irving Blum may have invented the concept of buying a masterpiece on layaway.)

I remind myself and my creative clients of stories like these all the time.

(Just FYI: Two spots left for the new light touch, micro-coaching program HERE).

Like that flashdancer, in order to triumph, we must first be willing to stumble.

We live in a world that constantly demand proof from us, but to reach that powerful closing argument — that “beyond a reasonable doubt” level of confidence — we’ve always got to start from that awkward beginning.

Tell a New Story \ Transform Your Life