They could not be more different.

One lives 2 years; the other 60-70.

One’s heart beats 600 times per minute, the other 30.

From conception, one gestates for just 20 days; the other, 660 (almost 2 years)!

Their social behavior also differs widely, ranging from solitary or small-group living to tightly knit family herds.

Even beyond this, their fear response is completely opposite: one flees danger instantly, the other is often curious or defensive.

I’m talking about the differences between mice and elephants, something I only recently considered during my latest animal adventures last month.

Yet they have something interesting in common with each other… and perhaps you and me as well.

I’ve often shared this story, which zoologists confirm is more than just a motivational metaphor.

Specifically, that if young elephants are chained to a stake that they’re too weak to break free from, even when they grow to a strength where they could easily free themselves, they don’t even try.

It’s the perfect analogy for Learned Helplessness, a term coined in the 1960s by Martin Seligman and Steven Maier in experiments with dogs subjected to unavoidable shocks, no longer trying to escape even when it was possible.

Resulting in insights about trauma, depression, and other human behavior, their work became the foundation for decades of research for why people don’t leave bad situations even when they can.

The same principle applies to caged birds that don’t fly away when the door is opened.

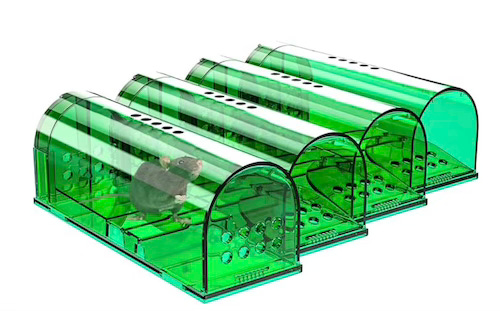

Over the last few weeks, I’ve now witnessed it a half dozen times myself, specifically with the country mice I’ve sometimes struggled to release into the wild.

Noticing that the mice had left behind several clues as to their presence—nibbling on a chocolate bar casually left on the kitchen counter, for example—it felt reasonable to take some measures against continued cohabitation.

Opting for humane traps—those where you catch and then release your unwanted housemate back into the wild, unharmed—seemed the most kindhearted solution.

That’s why I was surprised to see that most of the time, when the trap is open, rather than dashing towards freedom, the mouse often freezes.

Sometimes, I even have to shake them out, inspiring me to quote those profound lines from Rumi:

“Why do you stay in prison

when the door is so wide open?”

Rumi continues, offering the timeless reminder that we must:

”Move outside the tangle of fear-thinking.

The entrance door to the sanctuary

is inside you.”

All of this has inspired this month’s new meditation HERE, the theme of which is this universal struggle with Overcoming Resistance.

I’m reminded of the story of Hiroo Onoda (小野田寛郎,) the Japanese soldier who continued fighting World War II for nearly 29 years after it ended in 1945.

Onoda held out with three other soldiers, one who surrendered in 1950 and two others who were killed in 1954 and 1970.

Living on an island in the Philippines, he and his companions engaged in occasional guerrilla shootouts with the locals, surviving on coconuts, bananas, and whatever rice and cattle they could steal.

Even though they saw leaflets in 1945 announcing Japan’s surrender months earlier, they dismissed them as Allied propaganda.

Seven years later, in 1952, they didn’t even believe that airdropped letters from their own families were genuine.

After the last of his companions was killed in a shootout with local police, Onoda was left alone, still fighting a war that had ended nearly three decades ago.

Onoda in 1945

This month’s Transformation Book Club selection is one of my favorites, The War of Art by Steven Pressfield.

He is directly, perhaps almost exclusively, concerned with the topic of resistance, and how it is the great, ever-threatening enemy of creative work.

“Resistance will bury you.

It will become your default setting unless you consciously overcome it every single day.

Resistance will keep you in your comfort zone, but kill your soul.”

Pressfield frames the decision to move through resistance and actually do the creative work as a kind of surrender, one which leads to victory.

If you’d like to go on this journey with me, you can join us:

I’ve been actively exploring areas of resistance in my own life—hence this month’s meditation HERE—those spheres where Rumi would definitely tap me on the shoulder to ask “Why do you stay in prison when the door is so wide open?”

I’m drawing on Pressfield’s advice, of course, but also from poems that I love.

For example, here are the final two stanzas of a favorite poem by David Whyte.

Start Close In

Start right now

take a small step

you can call your own

don’t follow

someone else’s

heroics, be humble

and focused,

start close in,

don’t mistake

that other

for your own.Start close in,

don’t take

the second step

or the third,

start with the first

thing

close in,

the step

you don’t want to take.

You might be wondering what caused Onoda to finally surrender.

In 1974, he encountered Norio Suzuki, a Japanese globetrotter who told friends he was seeking “Lieutenant Onoda, a panda, and the abominable snowman, in that order.”

I have no idea if Suzuki found the latter two, but after four days of searching on the island, he located Onoda and they actually became friends.

Even so, Onoda still refused to surrender unless the order came from his commanding officer.

Suzuki returned to Japan, found the officer—who had long since retired from the military and become a bookseller—and brought him to the island so that Onoda could be given the formal orders relieving him of duty.

Nearly 29 years after the war ended, Onoda turned over not only his sword, but also a still-working military rifle and 500 rounds of ammunition, an assortment of hand grenades, and finally the ceremonial dagger his mother gave him to commit suicide with if captured.

It’s potentially all too easy to dismiss examples of resistance which are so extreme.

Mighty elephants can be restrained by little more than a shoestring; soldiers hiding out on a remote island refusing to surrender.

Yet how many of us are still fighting wars that were over decades ago?

Like my country mice friends, we’re often miserable in the cage—yet even more afraid to step into freedom.

As Pressfield writes, “Resistance will keep you in your comfort zone”—even when that’s inherently uncomfortable.

Rumi nudges us to “move outside the tangle of fear-thinking,” reminding us that “the entrance door to the sanctuary is inside you.”

Or, as Robert Frost wrote, “The best way out is always through.”

I’m particularly excited about this month’s Resistance exploration—even though I suspect there may be no easy answers.

Instead, as David Whyte tells us, it’s as simple as starting with that first thing close in, “the step you don’t want to take.”

Like me nudging my mice toward freedom, or Suzuki bringing proof the war is over, perhaps we can take that step together.