It was certainly not my intention.

I sincerely hope I’m NOT contributing to the problem.

I wasn’t aware of just how bad a reputation it has.

As an archetype, it definitely needs a new press agent.

You see, when I chose “Out of the Box,” as the theme of the June’s new meditation HERE, I only later realized I might be playing into the concept of the box as something one must escape.

Indeed, in Kim Krans’ Wild Unknown Archetypes Guidebook, here’s how she describes The Box:

We all live, to some degree, within the confines of The Box. This archetype represents everything that is known, anticipated, and expected. It holds us in place while simultaneously holding us back from our greatest visions. The Box is sneaky, insidious, and everywhere…

Even to me, someone who spent the better part of Memorial Day Weekend figuring out how to box up my mother’s first Etsy sale—that child’s rocker—this does sound a bit…extreme.

Picking the theme, I was mostly just amused by the experiential pun of thinking Outside the Box vis-à-vis my recent, very pragmatic UPS challenges.

At the same time, since I was contemplating what book to read for June’s Transformation Book Club—a perk of a premium subscription available HERE—my mind, still on boxes, recalled passages from one of my favorite inspirational texts, the genius choreographer Twyla Tharp’s The Creative Habit.

Tharp writes extensively about boxes being foundational to her creative process, and thus I feel compelled, like a good debate moderator, to let the other side of the argument be heard.

Tharp actually declares:

I start every dance with a box.

She writes the name of the project on the box, and as she develops the work, she fills it up with everything that’s part of its creative journey.

This includes “notebooks, news clippings, CDs, videotapes of me working alone in my studio, videos of the dancers rehearsing, books and photographs and pieces of art that may have inspired” her, as well as active research.

She shares that “For a Maurice Sendak project, the box is filled with notes from Sendak, snippets of William Blake poetry, toys that talk back to you.”

For her, what’s most important is that the box means she no longer worries about forgetting anything.

One of the biggest fears for a creative person is that some brilliant idea will get lostbecause you didn’t write it down and put it in a safe place.

I don’t worry about that because I know where to find it.

It’s all in the box.

For Krans and many others, the Archetype of the Box represents confinement; for Tharp it’s a treasure chest, one that promises freedom.

In some ways, the workshop I’m leading today for DailyOM’s first online global summit highlights both of these issues.

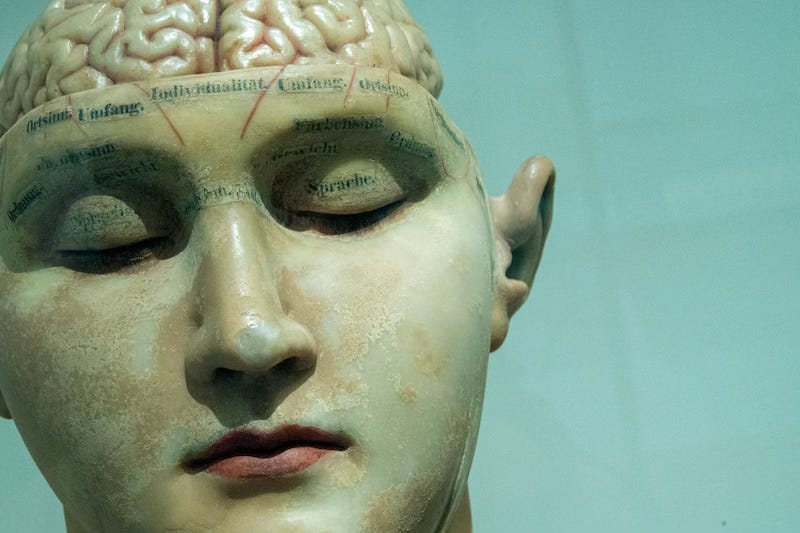

Without offering any spoilers, I can share that my topic—Rewrite Your Story: The Neuroscience of Reinvention—does discuss how our thinking can severely limit us.

Part of it is connected to the brain’s Reticular Activating System (RAS).

Since we’re often operating out of a default survival mode, we may be filtering our experience through an unhelpful lens.

This was echoed this week for me in reading John Assaraf’s newsletter, where he mentioned Sara Blakely in this context.

He wrote that “While everyone else saw pantyhose as a dying industry, she saw a $1 billion opportunity with Spanx.”

I cannot promise a complete rewiring of your brain leading you to become a billionaire, however, that’s exactly the kind of work I’ll be sharing live today.

I have also been thinking of another artist’s very different use of boxes, Andy Warhol’s Time Capsules.

Between 1974 and his death in 1987, Warhol filled 610 (mostly) cardboard boxes with items from his day to day life.

Not initially conceived as an art project, but simply as a way of cleaning up his office space, the project morphed into a life of its own.

Full of everyday ephemera, they include the banal (receipts, magazines, newspapers); the personal (fan letters, photos, invitations); and the curious to bizarre (McDonald’s wrappers and wigs) — even a mummified human foot.

The latter can be found in Box 21, along with 200 other items, and is even the subject of a meticulously catalogued book.

Unlike Tharp’s curated use of boxes to build a project architecturally, Warhol simply said of his Time Capsules:

“I just drop everything into the same size boxes.

When a box gets full, I seal it and put it away…

Someday somebody might want to see it.”

Some of the actual contents of Box 21

Other critics of the box include Malcolm Gladwell, who wrote — in a sentiment echoed by everyone from Deepak Chopra to Arnold Schwarzenegger:

“If everyone has to think outside the box,

maybe it is the box that needs fixing.”

Taking it a step or two further, the brilliant guerrilla artist Banksy wrote in his 2005 book Wall and Piece:

“Think outside the box, collapse the box,

and take a fxxking sharp knife to it.”

I know it’s meant as a metaphor—as did I in the new meditation HERE—but you have towonder whether all these folks had as challenging an experience with packaging as I did before PirateShip saved the day.

Of course, I’m a fan of “Out of the Box” thinking.

(Quite frankly, the entire DailyOM event is that at its core).

Yet it’s fascinating how the box itself—the most basic of structural containers—can represent such different things.

Krans summarizes her take on the archetype with:

“Everything within the box is known.

Everything outside the box is unknown.

That is why it is more comfortable to stay within its walls.

Choose freedom.”

Tharp however reaches a very different conclusion:

That’s the true value of the box:

It contains your inspirations without confining your creativity.

It occurs to me only just now that perhaps Twyla’s comfort with The Box somehow relates to her role as a choreographer.

Indeed, the philosophical term “ghost in the machine” comes to mind.

According to the American Psychological Association, the phrase describes a view in which “the mind is seen as a nonphysical entity (a ‘ghost’) that somehow inhabits and interacts with a mechanical body (the ‘machine’).”

Twyla’s genius is using the box of the body to convey the life that’s beyond it.

Or as Pierre Teilhard de Chardin famously wrote:

“We are not human beings having a spiritual experience;

we are spiritual beings having a human experience.”

In that sense, perhaps we are all boxed in — sometimes storing inspiration and archives inside, yet ultimately always beyond the confines of cardboard.