Apparently, I may not be as self-aware as I like to believe.

I learned this exactly yesterday, in a medically reviewed article in which I was interviewed as one of four experts HERE.

Specifically, according to Tasha Eurich, PhD, while 95 percent of people describe themselves as self-aware, only about 10–15 percent actually meet established psychological criteria for it.

I’d like to think I’m in that top 10–15 percent — but I’m wise enough to question whether I am, or whether I’m simply a tragicomic participant in the blind leading the blind.

Perhaps the quote I most identify with on the topic of writing — this month’s theme is Write It Down; Meditation HERE — is Dorothy Parker’s:

“I hate writing,

I love having written.”

A close second, though, might be one I’ve mentioned earlier this month by Joan Didion:

“I don’t know what I think until I write it down.”

It’s from her 1968 essay “Why I Write,” where she also shares another particularly memorable line about her process.

“Had I known what I was thinking, I would have had no reason to write it.”

For her, writing is not so much a medium of expression as it is a method of discovery.

This is actually fundamental to the FREE workshop I’m leading on New Year’s Day — only 10 days away! — where we’ll explore writing as a tool, first to figure out what we think and then to shape where we’re headed.

We’ll begin as archaeologists, in other words, and end as architects — shaping our lives through language.

Join us

I learned something else this week that surprised me.

James Pennebaker’s research on expressive writing began in the 1980s at the University of Texas.

Across many studies, participants who wrote about their thoughts and feelings — rather than neutral topics — showed measurable changes over time, including improved emotional processing, reduced stress indicators, fewer health-related visits, and improvements in attention and working memory.

A central insight from his work is that the benefits do not come from emotional outpouring alone.

Instead, they derive from the act of organizing experience into language.

It’s not that writing “fixes” your problems, but that when you take the time to translate raw experience into coherent language, the processes around that experience begin to change.

Mental load is reduced, and experience becomes more fully integrated.

None of this, however, was the surprise.

What surprised me was hearing that last year, on an American Psychological Association podcast, when Pennebaker was asked if people had “to write something every day to really experience the benefits,” he replied:

Oh my God, no. …

I write maybe two or three times a year

when something miserable is going on.

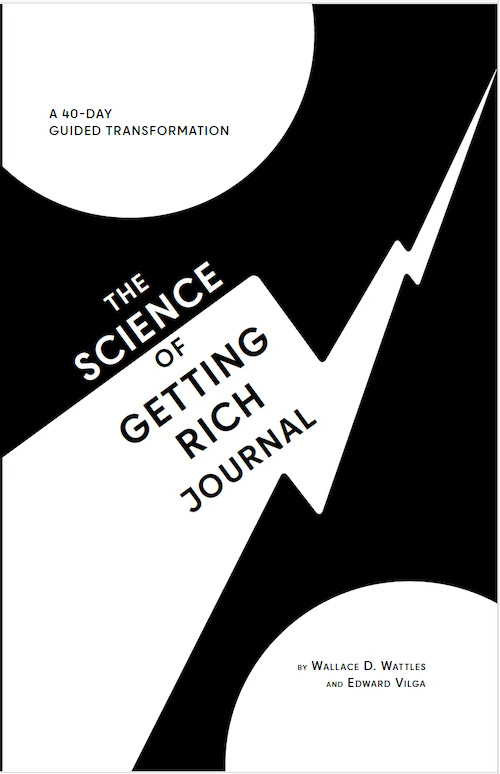

Before I forget to mention it — although we’re officially launching The Science of Getting Rich Journal in January, it’s already live on Amazon HERE.

Note: I’ve set the price at the lowest Amazon allows so you (and early readers) can get copies close to cost.

I wanted to let subscribers know before that changes — particularly if you’re still looking for a meaningful last-minute gift.

And if you do pick up a copy, I’d genuinely love to hear what you think.

Initially, I was inspired to share just two lines from a poem by Wislawa Szymborska —

I prefer the absurdity of writing poems

to the absurdity of not writing poems.

— but even though it’s a little lengthy, I liked it so much that I decided to offer it in its entirety.

Enjoy…

Possibilities

I prefer movies.

I prefer cats.

I prefer the oaks along the Warta.

I prefer Dickens to Dostoyevsky.

I prefer myself liking people

to myself loving mankind.

I prefer keeping a needle and thread on hand, just in case.

I prefer the color green.

I prefer not to maintain

that reason is to blame for everything.

I prefer exceptions.

I prefer to leave early.

I prefer talking to doctors about something else.

I prefer the old fine-lined illustrations.

I prefer the absurdity of writing poems

to the absurdity of not writing poems.

I prefer, where love’s concerned, nonspecific anniversaries

that can be celebrated every day.

I prefer moralists

who promise me nothing.

I prefer cunning kindness to the over-trustful kind.

I prefer the earth in civvies.

I prefer conquered to conquering countries.

I prefer having some reservations.

I prefer the hell of chaos to the hell of order.

I prefer Grimms’ fairy tales to the newspapers’ front pages.

I prefer leaves without flowers to flowers without leaves.

I prefer dogs with uncropped tails.

I prefer light eyes, since mine are dark.

I prefer desk drawers.

I prefer many things that I haven’t mentioned here

to many things I’ve also left unsaid.

I prefer zeroes on the loose

to those lined up behind a cipher.

I prefer the time of insects to the time of stars.

I prefer to knock on wood.

I prefer not to ask how much longer and when.

I prefer keeping in mind even the possibility

that existence has its own reason for being.

Back to Pennebaker and his only writing “when something miserable is going on.”

Unlike Didion, who writes to discover what she thinks — or those studies I’ve mentioned in past weeks where writing helps you commit to and reinforce your goals — writing has an entirely different purpose for Pennebaker.

In the interview he confides that:

“I use writing when I’m dealing with something that is ugly, unpleasant, painful.”

This dovetails with a wise Natalie Goldberg quote from Writing Down the Bones, our December Transformation Book Club Selection:

“Write what disturbs you,

what you fear,

what you have not been willing to speak about.”

When things are going well, Pennebaker feels no need to go deeper with them.

Personally, I can think of many reasons — capturing and savoring a memory; gaining understanding of how and why something succeeded — but that’s just not for him.

He remains quite confident about writing’s power and function, saying:

”You have all these bad things going on and then you use this method to get past it, and then next time something bad happens, I’ll use writing again.”

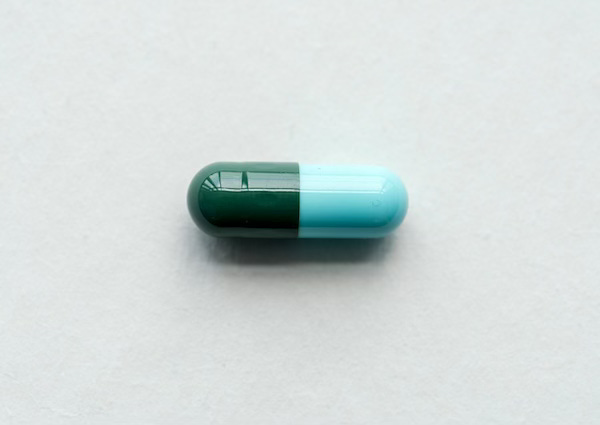

While I do think he’s shortchanging the value of Writing Things Down (again, December meditation HERE), I do like his metaphor for how writing serves him:

I’ve often thought of it (writing) as an antibiotic.

Honestly, when it comes to emotional chaos, I’d agree that taking pen to paper — or fingers to keyboard — is much more effective than penicillin.

I doubt my marketing team will seize on positioning The Science of Getting Rich Journal as an antibiotic.

It is, however, perfectly in tandem with another Natalie Goldberg quote:

“Writing is a way of being awake in the world.”

Indeed, I love an anecdote that Pennebaker tells about after a significant fight he had with his wife while on vacation.

Getting up in the middle of the night, he felt he should write to process the experience, but didn’t want to wake her.

Instead, he started “writing in the air,” with only his hands as his instruments, realizing “Wow, this works.”

He says that moment of discovery confirmed

“The real art is translating an emotional experience into words. And by doing that, that changes the way that experience is organized in the brain.”

In the article (HERE) where I’m cited as an expert, I’m quoted as follows:

“Self-awareness is built into the journaling practice — it’s the natural by-product of pausing to write things down,” Vilga says.

“Once thoughts are on the page, patterns and connections become visible that weren’t before,” he adds. “It helps us sort out the messiness of life and see what’s really unfolding.”

There are many ways to journal, from free writing to using prompts to writing down lists, but the real magic happens in consistency. “The more you engage with your own thoughts, the clearer — and more self-aware — you become,” Vilga says.

And while I — like roughly 90 percent of the population — may be deluded about my level of self-awareness, at least I’m on the quest for it.

As Oscar Wilde said:

“We are all in the gutter,

but some of us are looking at the stars.”

When it comes to journaling, however, the most interesting view — the one that is both awakener and antibiotic — is not so much upward as within.