Given that the view from my writing desk is semi-bucolic, it was a particularly unusual sight.

Looking out my window beyond the road, I see a dozen or so isolated trees, then a large grove—almost a mini-forest—on a community college campus.

The road itself is lightly traveled, only becoming a distraction if I’m trying to record a video or a meditation.

Throughout the day, an Amazon delivery vehicle might linger for a moment, but otherwise traffic flows freely.

It’s all extraordinarily uneventful.

In fact, I can’t recall any accidents or even vehicles breaking down—and certainly none like the one that pulled to the side on Monday morning: a 1930 Model T Ford.

To my untrained eye they look identical, but the car pictured above is actually a 1929 Model T.

You see, although I approached the driver to see if he needed help, it felt polite to compliment the car and ask its make and model, but snapping a photo of the breakdown felt way too intrusive.

(Hence the stock image).

A quirky senior citizen — sporting jeans, suspenders, and a well-groomed handlebar mustache — he radiated the kind of annoyed confidence of an athlete who’s tripped and is more embarrassed than injured.

The moment, however, did give me cause to wonder about this month’s theme of Adaptability — meditation HERE — and how surprise derailments can challenge us all.

Speaking of unexpected vehicles …

A podcast I listened to this week brought up a story that’s often exaggerated in pop culture but comes from a kernel of truth.

When the first Europeans arrived in the Americas, Australia, or other parts of the world, some have said that the indigenous people couldn’t even see the shipsarriving until it was too late.

That’s not exactly true.

There is, however, plenty of evidence that some of those Indigenous people did not immediately interpret the ships as “ships” — or even as human-made objects.

After all, how could they, never having encountered anything like them before?

Most scholarly accounts record them being initially perceived as strange clouds, floating islands, sea creatures, or simply “something unknown” and perhaps even heaven-sent.

Again, it’s not that their eyes were “unable to see” them in the literal sense.

Their rods and cones were firing perfectly well.

Instead, the phenomenon is about how our brains interpret raw sensory data.

All of us match things against existing categories (“boat,” “animal,” “cloud”; “dating red flags” vs. “keepers”) and if there’s no matching category, recognition can be slow, uncertain, or even deemed supernatural.

This wonky variation of adaptation happens to us all.

Speaking of which…

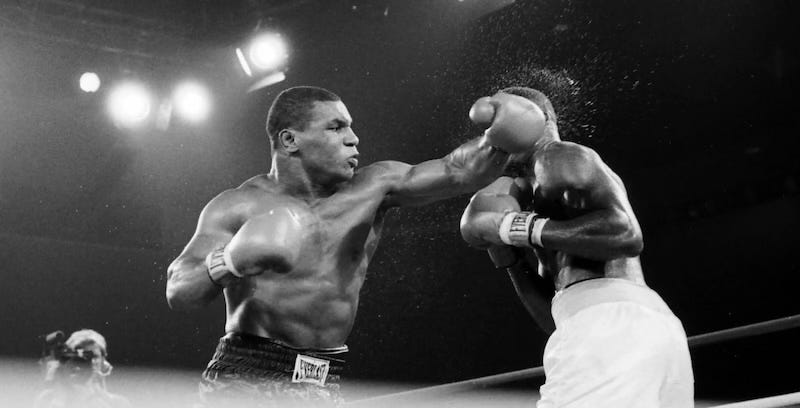

Right before a fight with Tyrell Biggs in 1987, a reporter asked Mike Tyson about his opponent’s strategy.

Tyson’s classic response:

“Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.”

No matter how carefully crafted or meticulous our best-laid strategies are, they can completely collapse the moment life takes its best swing at us.

Whether it’s the boxing ring or the boardroom, Tyson is clear that what ultimately wins battles isn’t just brute strength: it’s adaptability.

I did some further research on that “invisible ships” phenomenon.

But first, let me make clear that my motivations were more personal than historical.

I’ve been trying to process a series of instances of some folks I know “just NOT getting it,” seemingly indifferent to the Spanish galleons sailing into the bay.

The Anthropology model, called “Schema Mismatch,” helps explains this.

If someone has a strong mental model of you, the brain might filter out or distort any “category-breaking information” to preserve that coherence.

Unfortunately, rather than adapting, the safer route is simply to ignore.

Related to this is the phenomenon of dissociation and information gating.

While those ships weren’t yet directly threatening, they were unknown and therefore potentially dangerous.

The mind can respond to such situations with hesitation, resisting awareness of potentially uncomfortable truths in order to avoid emotional distress.

It simply disconnects from the data, herding the information away from conscious awareness.

It’s your basic freeze response, in other words, resulting in a kind of short-term amnesia.

Again, sometimes the brain’s default is to edit reality rather than actually adapting to it.

Connecting further with nostalgic car rides, there’s so much to love about this poem by Seamus Heaney.

He wrote it “remembering a windy Saturday afternoon” when he and his wife drove with the great Irish playwright Brian Friel and his wife Anne along the south coast of Galway Bay, coming upon “this glorious exultation of air and sea and swans.”

Beginning with the word “And” and entitled Postscript, it carries the energy of being a dashed-off communication to an old friend, totally heartfelt and almost spontaneous.

Postscript

And some time make the time to drive out west

Into County Clare, along the Flaggy Shore,

In September or October, when the wind

And the light are working off each other

So that the ocean on one side is wild

With foam and glitter, and inland among stones

The surface of a slate-grey lake is lit

By the earthed lightning of a flock of swans,

Their feathers roughed and ruffling, white on white,

Their fully grown headstrong-looking heads

Tucked or cresting or busy underwater.

Useless to think you’ll park and capture it

More thoroughly. You are neither here nor there,

A hurry through which known and strange things pass

As big soft buffetings come at the car sideways

And catch the heart off guard and blow it open.

This week I also learned that we may be on the receiving end of vehicles we ourselves cannot process.

This July 1st, astronomers from NASA spotted a miles-wide comet dubbed 31Atlas hurtling towards our solar system at the amazing speed of 130,000 mph.

This makes 31Atlas the fastest comet ever recorded.

Harvard astrophysics professor Ari Loeb and his team, citing “anomalous characteristics” in its profile—size, trajectory, and changing speeds—however, published a paper on July 16th positing that this “comet” might actually be an extraterrestrial spacecraft.

Again, this is coming from Harvard.

Other astronomers, though, such as Chris Lintott from Oxford, unabashedly describe Loeb’s reasoning as “nonsense on stilts.”

Soaring back from the outer limits of the solar system and cosmic speculation, I land again on my own quiet street, where it was soon clear that the owner of the 1930s Model T lived in the neighborhood.

His wife swiftly arrived on the scene, bringing a flatbed tow truck —the kind with a tilting ramp — that allowed them to gently roll the car up and secure it.

In our brief interchange, as I again complimented the car and expressed sympathy for their plight, she smiled and shrugged, saying,

“Breaking down is really no big deal

when you have your own flatbed.”

They flipped the narrative from victims to prepared players through their adaptability.

Indeed, we may all have trouble spotting the invisible ships in our experiences, but when life occasionally punches us in the mouth, it does pay to have an ice bag at the ready.

As Pema Chödrön wrote:

“The essence of bravery

is being without self-deception.”

As for 31Atlas, the current trajectory has the “comet” coming closest to us on December 19th, just outside Mars’ orbit.

That is, unless this “comet” has a pilot who suddenly changes its course.

Until then, we’ll have to wait and see—or perhaps more accurately, we’ll have to wait to witness whatever adaptation of reality our brains allows to observe.